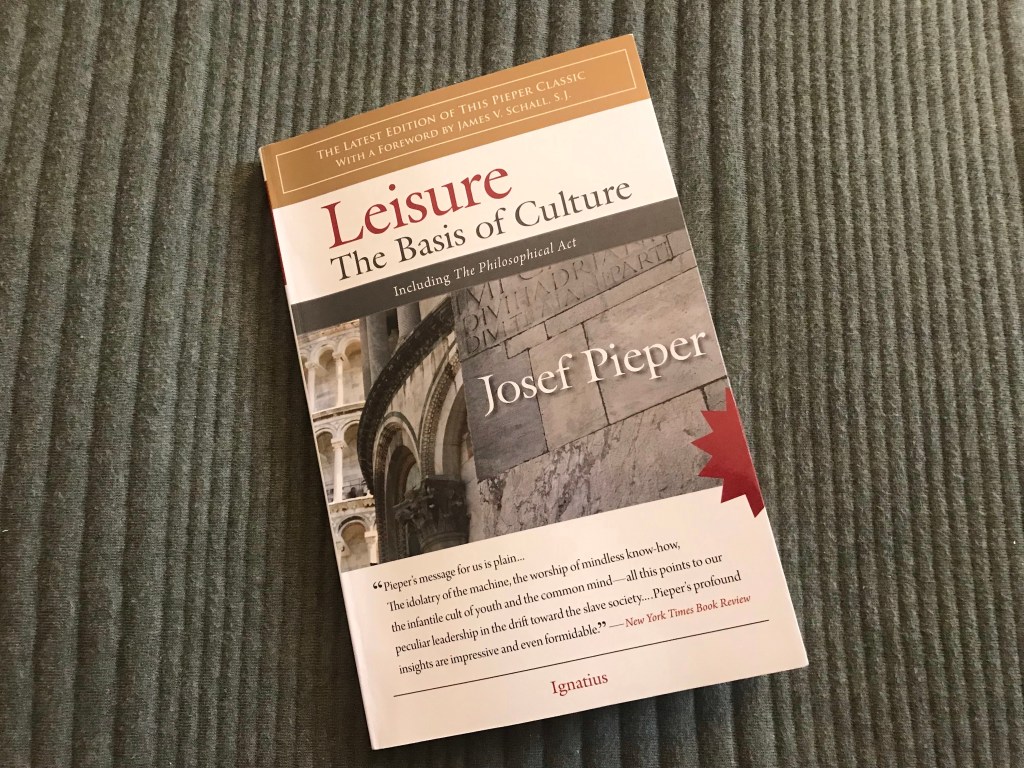

I want to wrap up this book study so I can move onto a new one. That doesn’t sound like a very good attitude, does it? This book is just not that exciting to me anymore. I started the study in January 2023. Shocking! And I will finish what I started.

Section IV opens up a can of worms that I don’t want to open. It seems to be pointing out differences of philosophies. Of which philosophies, I am not sure. I’m guessing Marxist ideas versus the ideas of the Catholic Church or Christianity in general.

He spends most of this section on what he calls, “Excursus on the Proletariat and Deproletarianization”. I don’t really want to go into it too much, so here’s my speedy overview:

Proletarians are people who are fettered to the process of work. They can be people from all levels of society, and there are different reasons why someone might be in this state of mind.

The author suggests combining three things in order to deproletarianize:

“…by giving the wage earner the opportunity to save and acquire property, by limiting the power of the state, and by overcoming the inner impoverishment of the individual.” (59)

Liberating a man from the process of work would require not only giving him opportunities to have activity that is not “work” (real leisure), but also that he’d be capable of leisure. He ends with the question: with what kind of activity is man to occupy his leisure?

In Section V, The main idea is that the core of leisure is celebration.

“Celebration is the point at which the three elements of leisure come to a focus: relaxation, effortlessness, and superiority of ‘active leisure’ to all functions.” (65)

He argues that celebration is man’s affirmation of the universe and his experiencing the world in an aspect other than its everyday one. The most intense affirmation of the world would be praising God. So, divine worship is the basis of celebration.

I thought this quote was interesting:

“ the vacancy left by absence of worship is filled by mere killing of time and by boredom, which is directly related to inability to enjoy leisure; for one can only be bored if the spiritual power to be leisurely has been lost.” (69)

I can remember being bored a lot as a kid. Sometimes I just didn’t know what to do with myself. There were many things I could do, but I couldn’t decide what I wanted to do. It makes sense to me that I would be confused or indecisive without having much self-knowledge, without a connection to God, and the trust in His guidance. I can still feel that way occasionally, but much less often as an adult because when I have an inability to enjoy leisure, I fill the time with work. This also makes me think about my YouTube problem. Is “the vacancy left by absence of worship filled by mere killing of time” in the form of scrolling on YouTube?

Solution: worship